In the contemporary spiritual landscape, few concepts suffer as much from reductive interpretation as brahmacharya. Whispered in yoga studios and spiritual circles, it is almost universally understood as celibacy a rigid renunciation of the body, sexuality, and worldly pleasure. This understanding is not merely incomplete it obscures the profound wisdom that lies at the heart of this ancient yogic principle. To truly understand brahmacharya is to discover not a denial of life, but an invitation to live more consciously, more powerfully, and more aligned with the deepest currents of existence itself.

The word brahmacharya emerges from Sanskrit as a composition of two luminous concepts: Brahman (the ultimate reality, the divine consciousness underlying all existence) and carya (conduct, movement, practice). Literally translated, it means “movement toward the divine” or “walking in the presence of God.” It is not the elimination of life; it is the directed channeling of life force toward the sacred.

Read This Article Also: benefits of brahmacharya

The Etymological Gateway: Understanding the True Meaning

To misunderstand a word is to misunderstand the reality it describes. The traditional Sanskrit definition reveals layers of meaning that Western translation cannot capture. The Darshana Upanishad defines brahmacharya as “the constant application of the mind in the path of becoming Brahman.” This is not a prohibition; it is an orientation a turning of consciousness toward what is eternal, real, and infinitely valuable.

The ancient yogic texts distinguished brahmacharya from mere bachelorhood or celibacy, which they termed caelebs an unmarried state. Brahmacharya encompasses something far more subtle and encompassing. It involves the regulation of all sense organs (the indriyas) in thought, word, and deed. It is the mastery not merely of sexual energy, but of all energetic expressions of the self the control of the mind, the direction of speech, the governance of action, and the management of attention itself.

This distinction is crucial. A person might practice celibacy while remaining enslaved to anger, greed, gossip, or mental corruption. Conversely, one practicing true brahmacharya might lead a householder’s life married, sexually active, engaged in the world yet remain centered in conscious awareness and spiritual purpose. The Charak Samhita, the classical Ayurvedic text, emphasizes this point with remarkable clarity brahmacharya is not always abstinence from sexual activity, but rather practicing sexual acts in a disciplined manner as mentioned in the sacred sciences.

The Katha Upanishad offers a timeless metaphor that illuminates this truth. In instructing the student Nachiketa, the Lord of Death (Yamaraja) teaches Know this self to be the rider. The body to be the chariot. The buddhi, or intellect, to be the charioteer, and the manas, or lower mind, to be the reins. The indriyas, or the senses, are the horses, and the vishayas, the sense objects, are the path on which they run.

Brahmacharya, in this framework, is the art of being a skilled charioteer not by starving the horses of their nature, but by directing their energy with wisdom and purpose. The horses must run; the question is whether they gallop wildly in all directions, or whether they move in measured harmony toward a meaningful destination.

The Classical Yogic Texts: Brahmacharya as Foundation

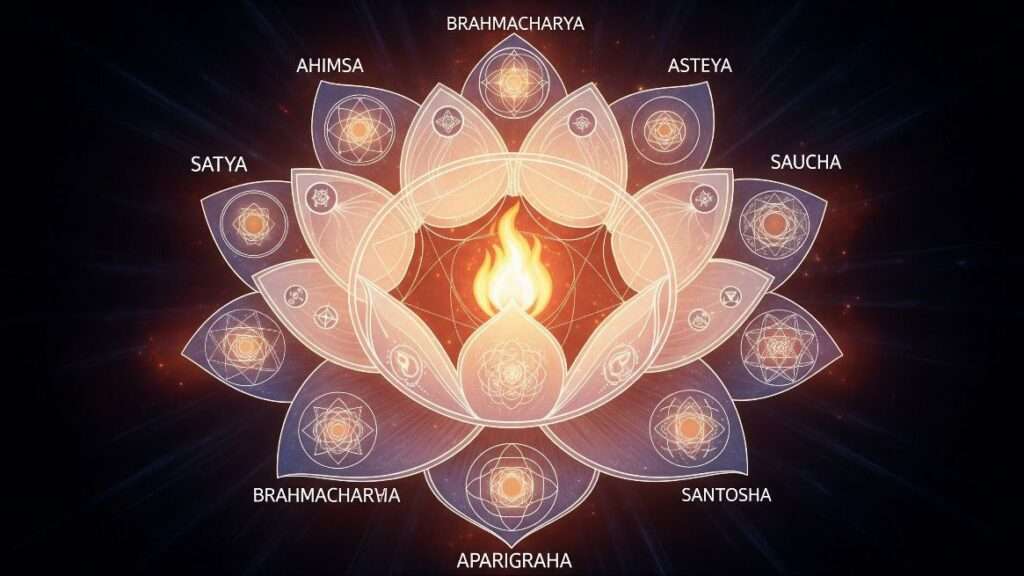

In the eightfold path of yoga (ashtanga yoga) codified by the sage Patanjali in the Yoga Sutras, brahmacharya appears as the fourth of the five yamas the ethical principles that form the first limb of yogic practice. The yamas are not commandments imposed from without, but universal moral axioms that reflect the nature of reality itself:

- Ahimsa (non-violence)

- Satya (truthfulness)

- Asteya (non-stealing)

- Brahmacharya (moderation; conservation and wise direction of energy)

- Aparigraha (non-possessiveness)

Patanjali’s sparse, profound style leaves the interpretation of brahmacharya open, yet the commentarial tradition clarifies its essence. The Yoga Bhashya, attributed to Vyasa (or written by Patanjali himself according to some scholars), explains that energy is conserved when attention is withdrawn from sensory pleasures. This withdrawal is not rejection but redirection from the periphery of sensation to the center of consciousness.

The practice becomes a form of intelligent energy management. Consider the dissipation of mental energy through rumination over past events, anxiety about the future, replaying conversations, or rehearsing scenarios that may never occur. The same mental faculty that exhausts itself through these patterns can be channeled toward meditation, study, creative work, and spiritual realization. This is brahmacharya in practice not the denial of thought, but the conscious direction of thinking toward what nourishes the soul.

The classical texts understood brahmacharya as foundational to all spiritual advancement. The Shiva Samhita, a text on tantric yoga, states that one of the primary causes of premature death is the dissipation of vital energy. The yogi who preserves this energy not through repression, but through wise channeling preserves the very fuel of spiritual transformation. The conservative channeling of veerya (vital generative energy) into tejas (spiritual radiance) or ojas (spiritual power) becomes, in the metaphor of the ancient masters, like oil that rises in a wick to burn with steady, glowing light.

Brahmacharya in the Upanishadic Vision: The Path to Self-Realization

The Upanishads, the philosophical core of Vedic wisdom, embed brahmacharya within the broader context of self-realization. The Chandogya Upanishad, one of the oldest and most revered texts, teaches that the ultimate goal of spiritual practice is the recognition of the Self (Atman) as identical with Brahman the infinite, eternal consciousness that is the source and substance of all existence.

In the eighth chapter of the Chandogya Upanishad, we find a remarkable passage that places brahmacharya at the gateway to liberation:

- A wise man, through Brahmacharya and realization, leaves this world and

- attains Brahmaloka. There he merges with the flame his own essential light.

- That light is the Self, the fearless, the immortal Brahman.

Notice the pairing: brahmacharya is not sufficient alone it is joined with direct realization. Yet it is presented as the gateway the necessary preparation that purifies the mind and frees the energy required for transcendent understanding.

The Upanishads teach that desires themselves are not inherently false. Rather, they become veiled by ignorance, by the illusion of separation, by the false identification with the limited body and mind. Brahmacharya does not destroy desire; it transforms it. The Chandogya speaks of the “desires that are true but covered by falsehood.” Brahmacharya removes the covering, revealing the deeper truth that all desire, at its root, is the soul’s yearning for reunion with the infinite what the Upanishads call moksha, liberation.

One who practices true brahmacharya begins to understand that sensory gratification is a pale shadow of the joy that comes from direct contact with one’s true nature. The Chandogya Upanishad describes the realized being who “knows the Self as Brahman” as living in absolute fulfillment “What can he desire? What can he lack or grieve for in this world?” This is not the flat, diminished existence of one suppressing desires, but the radiant aliveness of one who has discovered a joy so complete that lesser pleasures simply cease to attract.

The Transformation of Energy: Veerya, Tejas, and Ojas

The yogic and Tantric traditions develop a sophisticated understanding of how energy operates in the human system. This understanding bridges the gap between the abstract philosophy of the Upanishads and the practical lived experience of the practitioner.

Veerya the vital generative force, particularly associated with sexual energy is understood not as something inherently impure, but as one of the most powerful currents of life force flowing through the body. In an unconscious person, this energy disperses through compulsive sexual indulgence, fantasies, and emotional reactivity. The conservative channeling of this force becomes the foundation for what the ancient texts call ojas a kind of spiritual nectar or radiant spiritual power that accumulates in the subtle centers of the body, particularly the brain.

This is not mystical fancy but a precise observation of how consciousness functions. When sexual energy is not compulsively expelled, it can be transmuted through yogic practices meditation, pranayama (breath work), mantra recitation, and the contemplation of sublime truths into tejas (spiritual radiance) and ojas (spiritual power stored in the subtle anatomy). A person abundant in ojas possesses qualities that the texts describe with lyrical precision lustrous eyes, a magnetic aura, clarity of thought, emotional stability, and the ability to influence others through mere presence and few words.

Swami Vivekananda, the great 19th-century Hindu philosopher and yogi, spoke of this transformation with scientific directness: “Power comes to him who observes unbroken brahmacharya for a period of twelve years. Complete continence gives great intellectual and spiritual strength.” He understood brahmacharya not as weakness or denial, but as the accumulation of tremendous power power that could be directed toward the highest aims of human existence.

The conservation of energy through brahmacharya is not unique to sexuality. It applies equally to the mental and emotional realms. The person who gossips endlessly, who is pulled into every drama, who speaks thoughtlessly, who engages in unnecessary conflicts such a person leaks energy constantly. Brahmacharya in thought means the disciplined direction of mental attention toward what elevates consciousness. Brahmacharya in speech means words that nourish, heal, and illuminate rather than words that wound, confuse, or manipulate

The Eight Limbs of Brahmacharya: A Comprehensive Framework

The deeper yogic texts elaborate brahmacharya into eight progressive practices, each drawing one deeper into conscious living:

- Smarana (remembrance): Withdrawing the mind from sexual fantasies and dwelling instead on divine thoughts, spiritual teachers, and sacred truths.

- Kirtan (singing, speaking): Refraining from sexual conversation; instead, engaging in speech that elevates discussion of philosophy, poetry, spiritual knowledge.

- Keli (play): Avoiding amorous sports and flirtation; instead, engaging in activities that build spiritual community and truth.

- Prekshan (looking): Training the eyes to see the divine in all beings rather than regarding others as objects of desire or possession.

- Guhya-bhashana (secret conversation): Avoiding intimate conversations designed to create attachment or dependency; instead, maintaining clarity and healthy boundaries.

- Sankalpa (intention, thought): Releasing the mental resolve to engage sexually; instead, cultivating the intention to grow spiritually.

- Adhyavasaya (attempt): Refraining from physical approaches designed to lead to sexual contact.

- Kriya (action): The physical practice of abstinence or, for householders, the conscious, purposeful engagement in sexual activity aligned with spiritual values.

These eight practices reveal a startling truth: the practice of brahmacharya is not primarily about what you don’t do, but about where you direct your attention, intention, and energy. The ancient teachers understood that consciousness follows attention, that energy follows intention, and that transformation happens through the patient redirection of these fundamental currents of being.

Brahmacharya and the Householder Path: A Contemporary Vision

One of the most liberating insights emerging from contemporary interpretations of brahmacharya is its applicability to married life and sexual engagement. The classical texts themselves offer this opening. The Charak Samhita specifies that brahmacharya does not require absolute avoidance of sexual activity only that such activity be engaged in consciously, with purpose, moderation, and alignment with spiritual values.

For the student (the brahmacharya ashram), brahmacharya might indeed mean celibacy a complete dedication to learning and spiritual development. But for the householder (the grihastha ashram), brahmacharya takes on a different form. It becomes the practice of conscious sexuality sexuality engaged in with awareness, love, and purpose rather than compulsion, addiction, or the mere pursuit of sensation.

A marriage built on the foundation of brahmacharya principles becomes something sacred. The partners approach each other not as consumers seeking gratification, but as spiritual companions supporting each other’s growth. Sexual intimacy, when approached with this consciousness, becomes not a distraction from spiritual practice but a form of spiritual practice itself an expression of the divine through the human, a means of experiencing the other not as an object but as a manifestation of infinite consciousness.

Energy management in a relationship becomes a dance of conscious giving and receiving. The practitioner learns to distinguish between genuine intimacy, which nourishes both partners and deepens their spiritual connection, and compulsive entanglement, which depletes energy and clouds the mind. This is brahmacharya lived in the world not the denial of human connection, but its elevation to a conscious and spiritually purposeful form.

Brahmacharya in Modern Life: Beyond the Monastic Model

Contemporary society presents brahmacharya with unique challenges and opportunities. We live in an age of unprecedented sensory bombardment advertising designed to trigger desire, entertainment engineered for compulsive consumption, social media structured to create emotional dependency, and a culture that often equates self-indulgence with freedom.

Yet in this very context, brahmacharya becomes profoundly relevant. It offers a counter-cultural wisdom: that true freedom lies not in the multiplication of desires, but in the clarification and conscious direction of energy toward what truly matters.

Practicing brahmacharya in thought today might mean:

- Setting boundaries with devices and digital media rather than being passively consumed by them

- Cultivating discernment about what mental content truly nourishes versus what merely stimulates

- Withdrawing attention from compulsive thought patterns worry, rumination, planning and redirecting it toward present-moment awareness

- Developing the discipline to maintain focus on meaningful work rather than being scattered by endless distraction

Practicing brahmacharya in speech today might mean: - Speaking with awareness rather than reactivity

- Declining participation in gossip and unnecessary negativity

- Offering words that uplift, clarify, and heal

- Maintaining boundaries around intimate information rather than compulsively sharing

- Practicing brahmacharya in action today might mean

- Engaging with food mindfully rather than eating compulsively

- Using entertainment and leisure consciously rather than as escape

- Establishing boundaries in relationships that honor both one’s own energy and that of others

- Directing creative energy toward meaningful work and service rather than frivolous pursuits

In this light, brahmacharya becomes not a harsh restriction imposed by external morality, but a conscious choice rooted in self-love and wisdom. It is the recognition that energy is finite and precious, and that where we direct it shapes who we become and what we create in the world.

The Spiritual Alchemy: From Restraint to Transcendence

Perhaps the most profound aspect of brahmacharya is that it is ultimately not about restraint at all or rather, restraint is only the first stage. True brahmacharya is a transformation of consciousness itself.

When practiced with sincerity over time, brahmacharya naturally produces what the texts call vairaya a kind of dispassion not born of suppression but of genuine insight. The practitioner begins to see through the illusion that sensory pleasure can provide lasting fulfillment. This is not moral judgment but direct realization. Having tasted both the compulsive dissipation of energy and the profound peace that comes from its conservation, the practitioner naturally gravitates toward what nourishes the deepest self.

The Bhagavad Gita describes this transcendent stage beautifully:

- The objects of the senses turn away from the abstinent man, leaving the longing behind, but this

- longing also turns away after he attains Self-realization.

Brahmacharya is the bridge toward Self-realization. It is the clearing of the inner sky so that the light of consciousness can shine without obstruction. In the beginning, it requires effort the conscious redirection of habit and impulse. But in the end, it becomes effortless, the natural expression of one who has glimpsed the infinite nature of their own being and finds all lesser things naturally falling away.

Read This Article Also: Meditation and japa benefits

Conclusion :

To live brahmacharya is to answer a profound question: What is the highest use of my life force? Not: “What must I deny?” but “To what sacred aim will I direct my most precious energies?” It is a practice that honors the body while transcending identification with it. It embraces the fullness of human experience sexuality, emotion, creativity, connection while refusing to be enslaved by any of these. It recognizes that we are not primarily consumers seeking endless gratification, but souls on a journey toward awakening.

In a world that constantly encourages us to disperse our energy in pursuit of pleasure, status, and possession, brahmacharya offers a revolutionary alternative: the conscious concentration of energy toward the discovery of our true nature. It is not life-denying but life-affirming an affirmation of what is most deeply real and valuable within us.

The literal translation of brahmacharya as “walking in God-consciousness” reveals the true aim. It is not the diminishment of existence but its divinization the transformation of a human life into a conscious expression of infinite awareness. In this context, every choice becomes spiritual practice. The discipline of attention becomes meditation. The direction of energy becomes yoga the union of the individual will with the cosmic will.

This is brahmacharya: not a cold asceticism but a passionate dedication to what is eternally true. Not a denial of the world but a refusal to mistake the world for reality. Not a narrowing of life but an infinite expansion of it the recognition that within this very body, in this very moment, dwells the divine consciousness from which all existence flows. To practice brahmacharya is to walk that path, with every breath, every thought, every action toward the light from which we came and toward which, finally, we return.